Humans have been searching for solutions to mouse infestations for millennia. These persistent pests have plagued civilizations across the globe, sparking innovation in methods to protect food, belongings, and health from rodent damage.

Late Upper Paleolithic Era: No grains, No Gains

The common house mouse (Mus musculus ) population began to spread from its native homeland of South Western Asia to the Mediterranean and Middle East, following the development of agrarian lifestyles and grain storage around 14,000 years ago. See “How The House Mouse Took Over The World” for more information on how the house mouse became a global nuisance.

Mesolithic Era: The Cat’s Out Of The Bag

Love your cat? Thank a mouse! Our feline friends were first domesticated in the Middle East 10,00-12,000 years ago in response to the need to control rodent populations after the introduction of house mice. Cats served us by protecting our stored grain from mice. In true cat fashion, historians and archaeologists believed that they domesticated themselves: inviting themselves into human homes and villages in search of rodent prey and were provided with easy meals and a warm place to stay.

Ancient Greece

The first recorded description of a mouse trap occurred in the ancient Greek poem, The Batrachyomachia, a parody of the Iliad featuring Frogs and Mice. Its exact age is unknown, but it is believed to have been written somewhere between the 6th and 4th century BCE. The description of the trap is minimal, save for it being a wooden contraption and a “destroyer of mice”.

Ancient Egypt

Evidence of mouse traps existed as far back as 4,000 years ago in Ancient Egypt. Small torsion traps were unearthed from the tomb of Khety, which were believed to target mice and keep them from gnawing on the items in his burial chamber. A variety of different styles of mouse traps have been recovered from ancient Egypt throughout the years, including clap-net traps (1550BCE).

Middle Ages and The Renaissance

Terriers

Though dogs had been domesticated long before cats, their prowess as ratters and mousers was under-utilized until The Middle Ages in The United Kingdom, when the first terriers were bred. Terriers were selectively bred for their instinct to kill smaller prey, as well as their small body size. A well-trained terrier is a ruthlessly efficient killer. A terrier named Billy from 1820 holds the record for the fastest canine rodent catcher, dispatching 4,000 rodents in 17 hours (that’s almost 4 rats per minute!)

Terriers remained in common use as rat catchers through the 1950’s, when rodenticides increased in popularity, but their ratting careers may soon see a comeback, as some urban areas are bringing them back as rat control in an effort to control rodent problems without pesticides.

1800’s: “Build a better mousetrap, and the world will beat a path to your door”

Since its inception in 1838, The United States Patent Office has granted over 4,400 mouse trap patents. That’s more than any other invention! The disproportionate representation of mousetrap patents can be traced back to a famous 19th-century essayist, Ralph Waldo Emmerson, who is credited with coining the popular idiom, “ Build a better mousetrap, and the world will beat a path to your door.” Though the metaphor itself is paraphrased, the sentiment remains the same: it is a challenge to innovate solutions to everyday problems that American innovators took to heart, with mixed results.

Royal No.1: 1879

The first lethal mouse trap patent, the “Royal No. 1” was submitted by James M Keep in 1879. The design was similar to a wild game or bear trap, with sharp, cast iron “jaws” that clamped shut when triggered. They were unusually ornate contraptions, often featuring decorative embellishments and metal latticework. Today similar, less decorative versions of this invention made of plastic are still in production.

Little Nipper: 1898

The Little Nipper is the prototype we think of when we picture a mouse trap. Its flat, wooden base and spring-loaded design are still in use to this day. The Little Nipper snaps closed in 1/38,000 of a second, a record still yet to be beaten by any modern mousetrap.

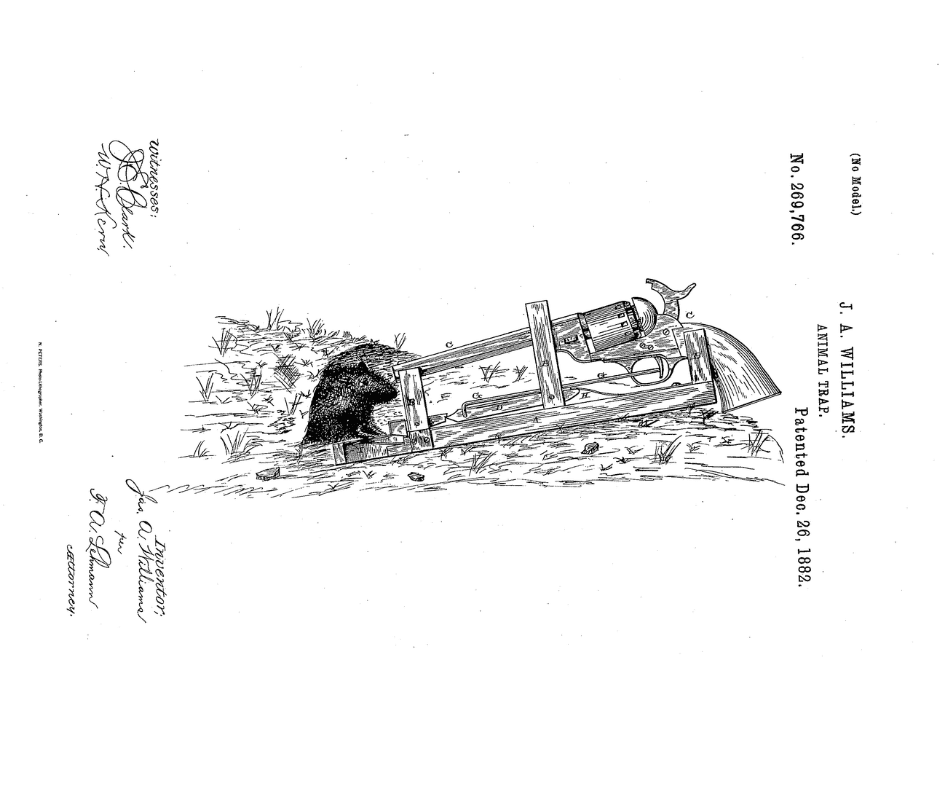

Some Ideas Were Better Than Others

All 4,400 mouse trap patents can’t be winners, but we’ll give some credit for style (or at least a good laugh). We hope it goes without saying, but please don’t try these at home.

Some, such as an 1882 patent titled “Animal Trap #4”, which consists of a loaded pistol or revolver is mounted onto a wooden frame, didn’t quite cut it. When an unfortunate rodent steps on the treadle, a spring level is activated and pulls the trigger. Unsurprisingly, this design never caught on. Perhaps they “shot themselves in the foot” by failing to consider safety and what would have undoubtedly been an unpleasant cleanup.

1900’s

Though many patents were granted from the late 1800’s-present, much of mouse trapping remained static. Some, such as Austin Kness, devised plans for a “ humane mousetrap” in the 1920’s that could catch and release multiple live mice at a time, but it never gained the type of traction that the more popular snap designs had.

Mid-Century: Out Of Sight, Out Of Mind

By the 1950’s, mass production had lowered material enabled snap traps to become disposable. Now, the more squeamish among us were able to simply toss the deceased mouse and trap in the garbage and set a new one, rather than having to clean and reset the same traps.

Bait traps also began to rise in popularity in the 1950’s with the advent anticoagulant rodenticides like Warfarin. Warfarin was considered the “first generation” of anticoagulant rodenticides. It disrupts the blood clotting process in the animal’s body, causing the rodent to die within a few days of ingesting the poison. Ever the survivors, mice, and rats began to become resistant to Warfarin by the 1960’s, so the switch was made to other anticoagulants like diphacinone and coutmatetralyl, which kill a rodent over multiple feedings as toxins build up in their body. Mice and rats again became resistant to these chemicals.

1970’s: Second Generation of Anticoagulant Rodenticides

Second generation anticoagulant rodenticides (SGARs), such as brodifacoum, bromadiolone, difethialone, and difenacoum, were developed and introduced to the market in the 1970’s, after rodents had built up an immunity to the anticoagulant rodenticides of the 1950’s and 60’s. SGARs are much more potent than their first-generation counterparts, and can kill in a single dose. These materials proved to have very high secondary poisoning rates for children, pets, and non-target wildlife such as birds of prey, and are no longer registered for consumer use.

Non- Anticoagulant Rodenticides:

Non-Anticoagulant rodenticides such as bromethalin, zinc phosphide, and cholecalciferol have since taken the place of anticoagulants as the active ingredients in rodenticides. These materials have a much lower risk of secondary poisoning for wildlife that may consume a poisoned mouse, such as owls, hawks, foxes, or cats.

SMART: A Modern Mouse Control Solution

Today, rodent control is about more than just catching mice—it’s about keeping them out of human spaces altogether. The SMART system offers a proactive approach to rodent control, using advanced detection technology to detect early rodent activity helps prevent infestations before they begin. By continuously monitoring for rodent activity, SMART helps protect your home without relying on traditional, reactive methods.

With SMART, you can have confidence that your home is protected, ensuring peace of mind and a pest-free environment.